When I entered graduate school, I first experienced the raw difference in quality art materials and supplies. There was such a huge distinction between the materials I used in the shop (the scene shop) to the materials I used in the studio, and I could immediately see the results in both different types of paints, and in different papers, and substrates.

It wasn’t an intentional experiment to find better quality, but it sold me on how quality makes a difference in the final product.After graduate school, I met an art instructor that explained a lot of technical differences in quality products, in particular in paint. I already knew that paint was primarily made up of a binder, pigment and a vehicle or solvent, but to see and understand what goes into making good paint was an eye-opening experience. Truly, there is nothing like finding the best paint to work with.

This doesn’t mean that there isn’t a place for all types and qualities of materials. Recycled objects, student grade materials, and low-grade drug store materials can all find a place in making art– good art. But, when you know the differences between a high quality product and a lower quality product, you can better choose how to spend your money and efforts on making art.

This doesn’t mean that there isn’t a place for all types and qualities of materials. Recycled objects, student grade materials, and low-grade drug store materials can all find a place in making art– good art. But, when you know the differences between a high quality product and a lower quality product, you can better choose how to spend your money and efforts on making art.

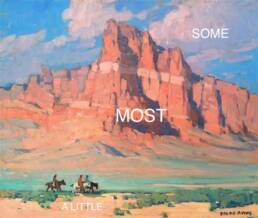

For paints in particular, better quality paints won’t necessarily have the highest pigment load, but often they will. Along with fewer or no fillers, the processing methods of better quality pigments from reliable sources may be more important than the total pigment load.

To test this for yourself…this test you are conducting is called a “relative tint test”

Purchase two different levels of quality of paint in the same hue and do the following: Mix an equal part of each color with the same amount of Titanium white, much more white than color. To be precise, the use of a scale measuring in grams is best, however using volumetric measurements such as “tea spoons” can work well too.

Use a palette knife to mix the paint well and apply to a substrate. I’d recommend trying this with acrylics or oils, as this test method is not that easy to do with watercolor. And for your first test, use a blue like Ultramarine or Cobalt, as they are more forgiving and easier to mix until you feel more comfortable with the testing.

You will be mixing two tints and comparing them to one another. In fact, anytime white is mixed into a color it is called a tint. You should be able to notice the difference in pigment quality between the two different quality levels of colors you purchased even as you are mixing them.

…anytime white is mixed into a color it is called a tint.

In addition, since the art material industry is dependent on other industries for pigment, like the automotive, architectural and aeronautic industries, sometimes a pigment becomes no longer available or changes in cost due to trends and needs of those markets. High quality paint, developed by a conscious manufacturer, will rely on as few substitution pigments in their paint lines as possible.

These manufacturers will communicate with the artists about what pigment is in the tube and if it may become no longer available. You should be able to see on your tubes or in the literature or website information from the manufacturer of paint exactly which pigments are in that paint. The notations can be confusing.

You will typically see a “P” which stands for pigment, and then there will be letters and numbers following to give you the full list of each of the pigments in that hue. This is another helpful way to compare hues from one brand to another. If you want a full listof pigment names, you can refer to the Weber Group.

For purchasing high quality panels, paper, canvas, paint – brushes, pastels, pencils, and colored pencils, there is a lot of experimentation and research you can do to find what will work for your type of art and budget.

Ask other artists what they are using, determine how durable you want your art to be for the long term and talk to your art material’s retailer.

If you have the interest, call a manufacturer to find out where they source their materials, talk to their research and development team or visit them in person. And lastly, if you have the ability to purchase a few types of brushes, or different papers, pencils or pastels to experiment for your own use. Sometimes the highest professional quality won’t be what you need while the studio or the student grade will suit your working style and budget much better.

Knowing the difference between quality levels is of the highest priority when creating art to be sold, or in becoming a professional artist. Your name will always be attached to your work. Collectors, galleries and museums purchase with the intent to keep your work for a very long time, possibly forever! Take time to learn what is best and it will be a wise investment for your work.

*****

Thank you Karyn! Karyn Meyer-Berthel is an artist and art material blogger as well as social media consultant. She was previously the online editor at American Artist and the lead administrator at WetCanvas!, as well as a DVD producer and director for artist painting DVDs. Karyn can be found around the internet, on Twitter https://twitter.com/#!/KarynMeyer and on the Dynasty Brush http://blog.dynastybrush.com/ and Ampersand Art Supply Blogs http://ampersandartsupply.blogspot.com/.

Click these links if you’d like to meet me on Twitter, and on Google Plus, Pinterest, and join in the fun at Fine Art Tips Facebook Fan Page! Please checkout my art too LoriMcNee.com, or find me on Instagram lorimcneeartist. ~Lori

Very often, using more expensive supplies is cost effective in the long run. Tinting strength is a good example of why. With a stronger, high quality paint, you will literally use less of it and the tube will last a lot longer than a student grade tube. You can test that objectively by doing two series of paintings and seeing what runs out faster.

Watercolor tinting strength can be tested by making washes with measured quantities of water and looking at how strong the resulting wash is. If just a little dab of a good artist grade watercolor produces a sky wash to cover most of the surface but you need a blob that’s a quarter of the tube to do that with a cheap student grade watercolor – you can see how much money you save using the better product. Especially the more often you use it.

Last, I have taught many beginners. I’ve seen them come in with cheap materials frustrated because they couldn’t reproduce an effect they saw in a painting they loved – when they used the technique accurately but the paint wouldn’t do what they wanted. This is one reason why experience is your key to understanding what art supplies do per medium. The chemistry in each medium is different. The binders and fillers and solvents are different. The handling qualities are different.

My suggestion for beginners is to get the very best they can afford, read up online before buying their materials and choose fewer colors to start. Three or four tubes of artist grade paint versus the 24 color student grade set will do two things. The beginner won’t be hampered by materials that don’t do what the book, video or teacher demonstrated, there’s one great benefit. The beginner will also find it a lot easier to get good color harmony with a small palette, all the mixtures will be unified rather than muddy.

I discovered this on the Winsor & Newton website when they recommended Lemon Yellow, Permanent Rose and Ultramarine as a starting watercolor palette. Just three tubes of artist grade watercolor and I got a full bright spectrum of intense high saturation mixtures plus a nearly infinite variety of muted and neutral hues. The “black” mixed from all three of those colors was a good satisfactory neutral but had a richness black paint from the tube doesn’t always have.

Last point to add on paint. Single pigment paints are more versatile and easier to control in mixtures than convenience colors involving multiple pigments. They give you the most control of your results. Once you’re familiar with the component pigments you might buy some convenience colors because mixing them every time is inconvenient.

I replaced Sap Green with Quinacridone Gold in one pocket watercolor set because I checked the pigments on that brand of Sap Green and found it was Quinacridone Gold with a single pigment blue already in the set. Mixing it meant I had the option of using other good Quinacridone Gold mixtures as well as the Sap Green, plus using it pure for glazes or as the yellow in a primary triad to give a different look than either of the yellows already in the set.

What that takes is time, practice, experimentation. You’ll find out what you like best in relation to your own style of work. Lightfastness is an issue too, but some of the better student grade paints are also lightfast. Lightfastness is not as big an issue if your final use for the art is to make a digitized image, then getting it to look good on the camera or scanner is more important. Lightfastness doesn’t matter as much inside bound journals either because the painting isn’t going to be exposed to light very often – fugitive pigments that faded in medieval and Renaissance paintings have stayed bright and clear when they were used in book and manuscript illumination. But the cheapest paints sometimes degrade with time as well as light, which is why children’s materials are so ephemeral.

If you want to keep your children’s artwork for a permanent keepsake, occasionally give them non toxic high quality lightfast student grade paints to work with. Set those works aside dated and signed, so they can show their grandkids when they grow up. Keepsakes are another thing where permanence may be important.

Hello Robert,

Wow, what a wonderful follow up to this article! I totally agree with your points. I too have witnessed beginners who get frustrated by using low quality materials. The brushes don’t cooperate, the paints don’t flow or cover properly. It is interesting what you can learn by just reading the labels. I also use Quinacridone Gold for glazing, but with oils. I still do wonder about the lightfastness of Alizarine Crimson…I have heard mixed reviews.

Thanks again for your thoughtful comment. It is a pleasure having you visit my blog, and I hope to see you here again. If you would ever like to guest blog, I’d be honored to have you!

Happy painting-

Lori

Really appreciate all this great info on quality paints. As a watercolorist, especially liked Robert Sloan’s advice. Thanks!

Hi June! Great to see you here. I really am glad Robert left us all such a valuable comment. I am glad it helped you.

Happy painting-

Lori

Great post, I fully agree!

I’ve completely replaced all of my materials from paints, stretcher bars, canvas, brushes, etc to business cards and studio lights to be the most eco friendly I can find. It took me about 18 months of research and another 12 months of testing and resourcing to get it right and find the best quality with as little impact. Even now I’m still refining to get it as good as possible.

I have a list of the materials I use on my website http://scottdenholm.com/environment/ 🙂

Regards

Scotty

Hey Scott! Thanks for sharing your wealth of information with us here. I would love to use your environmental findings from your blog and feature you in a post! What do you think? Your information is valuable and would help others and the planet too.

I have just ordered a bunch of Cobra paints myself…can’t wait to try them.

Cheers-

Lori

Hi Lori

That sounds amazing, I’d love to collaborate 🙂 When I was researching for eco materials I found that there were no websites or guides to help, specifically with fine arts. I think it would help a lot of artists looking for the same info!

Let me know how you go with the Cobras, I didn’t need to adjust too much to get used to them.

Regards

Scotty

Great Scott! I just emailed you…

L

I have two pet hates: cheap paints and cheap brushes.

I always encourage my students to buy a few high quality paints rather than a big selection of cheap ones for the same money. It’s not just about the paint quality, but I’ve noticed having a big set of colours actively discourages beginners from learning to mix colours. Often they don’t try, since something akin to what they want is probably available within the set. If they do try to mix there are so many colours to choose from it’s hard to know which to pick. Even if the mix works they’ve often forgotten which combination was used next time they need it. Much better to start with just a few colours and learn how those will combine, gradually adding extra colours to the paintbox as experience grows.

As for brushes: despite all my attempts to dissuade her, one of my students was addicted to cheap paint brushes for botanical watercolours. (I’ve no idea why – she was happy to buy best quality for all her other art materials!) Finally, in desperation, I put a good sable in her hand and asked her just to try it. After one brush stroke she exclaimed, “Ooh, it goes where you want it to!”

Enough said.

Hello Jackie,

I have never heard of ‘pet hates’ before, but I guess I share the same sentiments with you about cheap brushes and paints – lol. I too agree that it is better to work with a limited palette before adding too many pigments. This is a mistake that many novice artists make.

Ah, yes a good sable brush works wonders. In the past I have tried to skimp on brushes, only to regret the extra time and energy it took to complete a painting to my satisfaction. The extra cost of a good brush will payoff in the end!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts,

Lori

Nice post! I often read in different articles that as a beginner we have to use low cost art supplies like paints and brushes. But with this post everyone can understand the value of quality art materials rather than the quantity. Great piece of information. Thanks for sharing.

Happy to share! Glad this information helped you. I truly believe beginners need good tools to help them learn to create. Struggling with lousy art materials makes learning even more difficult!